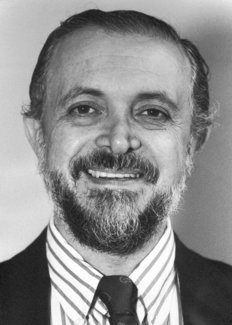

Mario Molina was a Mexican Chemist, and was the first Mexican-born scientist to receive a Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Born on March 19th, 1943 in Mexico City, Mexico, Molina was fascinated by science at an early age. He even went so far as to convert a spare room in his childhood home into a small laboratory, in which he fiddled with chemistry sets.

He spent many years working to earn a degree in physical chemistry, and even earned a Ph.D. in the subject. He spent time at schools in Mexico, the US, and even Germany. He attended:

- National Autonomous University of Mexico (Mexico)

- University of Freiberg (Germany)

- University of California, Berkeley (US)

His graduate thesis, Vibrational Populations Through Chemical Laser Studies: Theoretical and Experimental Extensions of the Equal-gain Technique (1972), described some features of laser

signals, including that, at first sight appeared to be noise – as “relaxation oscillations,” predictable from the fundamental equations of laser emission.

He did not, however, continue this

research as he did feel right about it morally.

I remember that I was dismayed by the fact that high-power chemical lasers were being developed elsewhere as weapons; I wanted to be involved with research that was useful to society, but not for potentially harmful purposes.

He worked with F. Sherwood Rowland in Irvine, California on the discovery of the threat of CFCs to the ozone layer in the stratosphere; As a result of their

work, laws were established to protect the ozone layer by regulating the use of CFCs. According to the Global Monitoring Laboratory, CFCs are nontoxic, nonflammable chemicals containing

atoms of carbon, chlorine, and fluorine. They are used in the manufacture of aerosol sprays, blowing agents for foams and packing materials, as solvents, and as refrigerants.

Molina and Rowland not only published their findings in 1974 in the journal Nature, but did their best to ensure that the issues addressed made their way into the public.

...we had decided to communicate the CFC – ozone issue not only to other scientists, but also to policy makers and to the news media; we realized this was the only way to insure that society would take some measures to alleviate the problem.

Sherry and I published several more articles on the CFC-ozone issue; we presented our results at scientific meetings and we also testified at legislative hearings on potential controls on CFCs emissions.

In addition to this work, he also made an significant impact in explaining the loss of ozone in the polar stratosphere. He did so while working at the Molecular Physics and Chemistry Section of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California.

Around 1985, after becoming aware of the discovery by Joseph Farman and his co-workers of the seasonal depletion of ozone over Antarctica, my research group at JPL investigated the peculiar chemistry which is promoted by polar stratospheric clouds, some of which consist of ice crystals. We were able to show that chlorine-activation reactions take place very efficiently in the presence of ice under polar stratospheric conditions; thus, we provided a laboratory simulation of the chemical effects of clouds over the Antarctic. Also, in order to understand the rapid catalytic gas phase reactions that were taking place over the South Pole, experiments were carried out in my group with chlorine peroxide, a new compound which had not been reported previously in the literature and which turned out to be important in providing the explanation for the rapid loss of ozone in the polar stratosphere.

For his work in the discoveries of CFCs in ozone depletion, Molina was highly regarded and received many awards, including a share in the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, alongside the colleagues he

had worked with in making the discovery. According to the Nobel Foundation the official motivation for the bestowment of the prize was, for their work in atmospheric chemistry, particularly

concerning the formation and decomposition of ozone.

The prize, just the same as other Nobel Prizes, was received in Stockholm, Sweden.

Sadly, Molina died on October 7th, 2020 in Mexico City, Mexico, due to a heart attack. May he rest in peace.

I chose to research Mario Molina because one thing that I always enjoy learning more about is science. It doesn't particularly matter the specific science, I just enjoy science in general. Out of all the people I had found, he was the only scientist, so I got to work finding out more about him. After finding out the basic background information of his work on discoveries with the ozone layer, I was immediately hooked, and proceeded to dig deeper. I do not regret this decision one bit, and I'm quite glad I stumbled upon this brilliant and kind individual.

Mario Molina and his colleagues brought to light the danger of CFCs on our environment, and helped make sure that the destruction of the ozone through CFCs was slowed. We can use his research and accomplishments as a guide for how to help protect our planet from being damaged. Perhaps by using fewer aerosols and refrigerants.